Does your production depend on Electric Submersible Pumps (ESP)? If so, are you doing everything possible to maximise run-life? Do you have a clearly defined ESP Management System? When was the last time you conducted an ESP Life Cycle Review?

A Life Cycle Approach to Maximising ESP Run Life

There are many excellent SPE Papers and articles about the “latest-and-greatest” in Electric Submersible Pump (ESP) technology developments. Some of these innovations help to improve run-life and some do not.

What I’ll be discussing in this article, however, is not the technology itself but the management of key processes typically found in companies operating ESPs, ones that directly impact run-life.

I’ll begin with my favourite analogy, the humble bicycle chain. We can all visualise a bicycle chain and understand that it only functions when all links are intact. If a link breaks, then no matter how hard you peddle, the bicycle has lost all power. Only one component has broken – not the wheels, the frame, tyres etc. – nevertheless, this failure affects the entire system, i.e. the bicycle. So we can say the bicycle has failed and, while we’re at it, let’s call the time between purchase and failure the service or “run-life”.

Now if we have several bicycles, over time we can determine some kind of average run-life. If we want to sound clever we could even start talking in more esoteric terms such as “mean-time between failure”, or MTBF. But I prefer to keep things simple, so in this article I will refer to “average” run-life.

(The main reason I try to avoid using the term MTBF is that over the years I have found that many companies – and indeed departments within companies – define it differently. Sometimes, though not always, this lack of clarity is deliberate, to skew the statistics in a favourable way.)

“There are lies, damned lies and statistics”[1]

For a chain to last several years it needs regular maintenance in the form of cleaning and inspection, and the links must receive regular doses of a suitable lubricant. When a link fails it must be replaced for the bicycle to function. The future run-life of the bicycle now depends on the longevity of the second weakest link, be it (literally) a chain-link or something else such as the tyres.

That sounds logical and, frankly, pretty obvious: attention to everything helps to maximise the bicycle run-life. So why don’t we do the same with ESPs?

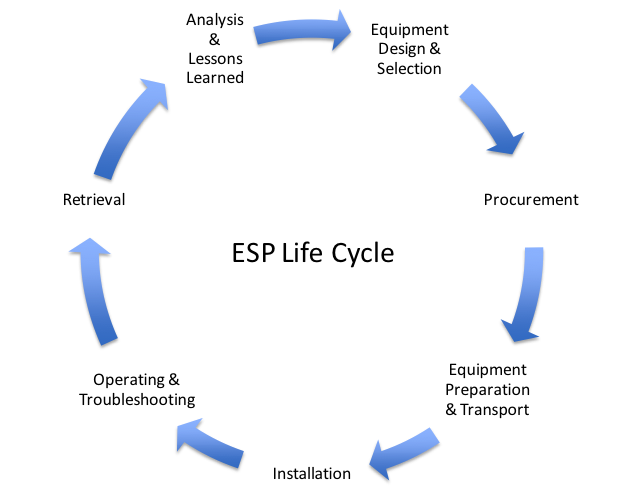

I began this article by stating I want to focus on processes that impact ESP run-life, so let’s name some. Figure 1 summarises what I call the ESP Life Cycle:

By now I think it’s pretty clear that I’m advocating a holistic approach to ESP run-life management because each element of the Life Cycle contributes to the overall run-life.

To illustrate my point I’ll use an example from many years ago. A series of premature ESP failures occurred in a Field, one that I had literally just been appointed to manage all sub-surface activities on. I’ll call what happened infant mortalities and define this as an ESP failure within 90 days of start-up, though in this case I believe all failures occurred within 30 days. The evidence from retrieved ESPs suggested severe over-heating of the motors.

Located in an environmentally sensitive area, this offshore Field had high-rate oil producers and relatively high-workover costs. For the Operator it was a prestige project, politically and financially significant, and so no expense was spared in terms of equipment quality.

As you can imagine, Management at the Branch Office responsible for this Field was not pleased about these sudden and completely unexpected failures, nor was Head Office. Clearly something needed to be done to rectify the situation, but what?

Coincidentally, the same technical team was also responsible for another ESP Field, also offshore but very mature, barely profitable and close to abandonment. Economics dictated that only refurbished equipment be run. Curiously enough, 4-6 year run-lives were common.

The first assumption was that the ESP Vendor had supplied faulty equipment (as far as I recall all motors originated from the same run). But then it was noticed that in each case flow past the motor had been less than 1 ft/s at the time of failure (API RP 11S4 recommends this cut-off for typical 30° API crude*) and in this Field, oil gravity from some producers was low, around 18-22°API.

(*Yes I know, not everyone agrees with this rather old criterion. They say with modern technology such limits are out of date, one can measure motor-winding temperature directly, use software to predict heat rise and even estimate longevity. Maybe, but I would argue that from a planning perspective, 1 ft/s is an extremely valuable flag. In my book, any operating condition that potentially comes even close to this limit requires further investigation, e.g. post-WO kill fluid unloading. And in this case, no one had even looked!)

Now it was clear, the combination of low velocity and moderately viscous crude resulted in insufficient motor cooling. But why did this happen? What went wrong in the system that allowed such a basic mistake to occur? And why only in the prestige Field and not the very mature one?

Let’s start out by blaming the ESP engineer employed by the Operator – after all, it was his job to check flow velocity past the motor during the design phase, wasn’t it? And while we’re at it, let’s also blame the ESP Vendor Application Engineer because he too, should have checked this. So the solution is easy: fire the ESP engineer and change ESP Vendor to one that gives better support.

Problem solved? No, of course not!!

Take another look at Figure 1, think about the processes and ask yourself, how many of the Life Cycle elements do you think somehow contributed to this particular failure?

Digging a little deeper, I found:

- The Operator was using this prestige Field as a training ground for young production engineers.

- None of the staff involved with ESP design/sizing had received any formal ESP training. Same thing for offshore staff responsible for starting and operating the ESPs – they also had not been trained.

- There were no Company ESP Standards or Procedures:

- Nothing to guide the ESP design/sizing process or any requirements for equipment limit checks.

- No ESP installation, commissioning or start-up procedures.

- No ESP performance monitoring and troubleshooting guidelines.

- The ESP engineer was motivated but inexperienced. He received neither direct technical supervision nor any kind of mentoring. So when he proposed to replace a conventional ESP completion set in 7” liner to one with a Y-tool (by-pass system) set in 9-5/8”, Management were quite pleased. They thought it was innovative because this would allow reservoir access, e.g. production logs, re-perforating, etc. (Note: No one had actually demonstrated a need for reservoir access, they just thought it was “a good idea”. And no one had thought about the potential impact of lower fluid velocity on motor cooling as a result of re-locating the ESP to the larger diameter of the 9-5/8” casing.)

- There was no system in place to actively monitor motor temperature and other critical ESP parameters. (Some Managers considered this information to be costly and superfluous. Why? Because no one had convinced them otherwise!)

- The Purchasing Department (based in Head Office, far from the Field) prided itself on getting the best possible price via a tendering process*. The ESP Vendor was squeezed so much there was little incentive to give any technical support.

(*I would argue that you can’t – and should not attempt to – treat ESP procurement and especially technical Support, as being the same as buying API tubulars but I’ll save that discussion for another day!)

- From the ESP Vendor’s perspective, this was a Customer that only purchased 1-2 ESPs each year. In short, the (already overstretched) Application Engineer had bigger fish to fry. Besides, more failures often means more Sales – until of course the point is reached when the Operator decides to change Vendors.

The list goes on, but I hope I’ve made my point. Each individual involved thought that he/she was doing a good job, and yet the system failed.

What about the other Field, why did ESPs there have very good run-lives? Apart from the fact that flow velocities across the motors were higher and average well water cuts were around 95-98%, (i.e. better cooling because water dissipates heat better than oil), the crude itself was closer to 30° API, the wells were shallower and… the young engineers were not interested in it. Furthermore, the workover crew was very experienced; most of them had worked on that Field for many years.

So from the perspective of the young engineers, attention from Senior Management (and hence future careers) could best be obtained by focussing on the prestige project. As they saw it, there’s not much glory working on an old Field that’s about to be abandoned. So they left it alone. And as a result, at least in this case, everything was fine.

The Bigger Picture

I think the above example demonstrates a multitude of system failures. These include the various process failures within the Life Cycle elements, for example the lack of ESP Procedures and any checks-and-balances. But it also illustrates another inherent challenge, namely that of managing interfaces.

Interfaces are natural boundaries. They can be external, say between Operator and ESP equipment provider, or internal, such as between departments. Groups on different sides of an interface are often subject to different goals, for example

- “We need to achieve an average ESP run-life of 4 years for this Field to be economic.”

- “The Workover Department has been tasked with cutting average ESP installation time by 2 days this year.”

- “We get rewarded for obtaining the lowest purchase price for goods and services.”

- “My manager says I have to sell 20 ESP units this Quarter or I’ll lose my job.”

Looking at the bigger picture, the obvious solution to improving ESP run-lives is to harmonise the goals. But as we all know, aligning goals that cross these interfaces is often easier said than done.

First, here’s an example of something that’s relatively easy to fix:

- Current Situation: An ESP Field Service technician is unable achieve a good wellsite splice of the ESP power cable splice because the Company Man is breathing down his neck every 10 minutes asking if he knows how much 4 hours of rig-time costs.

- Fix #1: Time for the Splice is identified in the WO Planning and communicated to all, including said Company Man. During splicing, all non-essential personnel leave the area, which is adequately lit, weather protected (as far as is practicable), etc.

- Fix #2: “No” wellsite splicing. (Or at least as few as possible.)

This, real-life example, appeared trivial to fix but in practice it wasn’t:

- Background: The Operator of a remote, onshore Field wanted to minimise ESP assembly make-up at the wellsite. This was not only to minimise installation time but also to reduce risk of operational error during make-up (Arctic conditions in winter). Vendors were therefore asked to make-up as many components as possible prior to leaving their Base.

- The Issue: A different Department was responsible for all transport logistics (not just ESPs). They hired a local trucking company whose flatbeds were not long enough; half-made-up ESP assemblies extended beyond the back of the trucks. Road conditions were poor and the ESP sections that protruded beyond the trucks were subject to excessive vibration, potentially damaging bearings and other internals.

- The Outcome? Not resolved – neither party was willing to change their position and Senior Management refused to get involved with a “local issue”.

Last example:

- Current Situation: “Poor” technical support from ESP Vendor.

- Fix #1: Bite the bullet and explicitly pay for support. (There’s no such thing as “free” support – you’re already paying for some support in the purchase price. But if you only buy a few units each year then you can’t realistically expect to receive the same level of attention as an Operator that buys hundreds.)

- Fix #2: “Incentivise” the ESP Contract. Make it financially more interesting for the Vendor to help promote run-life rather than sell more units. This might involve “renting” rather than purchasing ESPs. Whichever route you choose, it has to be a true win-win or it won’t be successful over time.

In my experience, the hardest interfaces to align are those that involve different divisions within the same Company. While it might be relatively straightforward to coordinate goals of say, Workover and ESP Design Groups, Procurement is often a completely separate Department/Division with a different reporting structure. The most likely way to effect a change in their goals is to convince someone higher up in the chain, often at CEO/Board level.

And how do you do that? Well, as the saying goes, first get your own house in order. I recommend conducting what I’ll call an ESP Life Cycle Review. Think of it as a kind of Baseline Audit: a review of current ESP-related documentation (Procedures, Standards, etc.), interviews with key personnel based on carefully calibrated questions and visits to local equipment Suppliers, Repair Shops, Storage facilities and of course the Wellsite.

This information, together with observations and impressions gained during the Review, help to establish the Baseline. That is to say, a Snapshot of where the Operator is in terms of managing ESP performance. This is then used to identify deficiencies (e.g. those missing Procedures), non-conformance (e.g. having Procedures but not adhering to them) and other opportunities for improvement. Returning to the bicycle chain analogy, it is a process of examining all the chain-links, trying to find the weakest ones – hopefully before they break.

For the Review to be truly effective it will need support from the top: the higher the better. Simply put, any Study will have more credibility – and therefore carry more weight – when Senior Management is seen to fully support it. This in turn is more likely to elicit at least tacit support amongst those (perhaps in other Divisions) who might otherwise be more sceptical and/or less cooperative.

(If you’re going to ask a Buyer to knowingly pay more for an ESP compared to current prices – in exchange (you hope!) for better technical support – then he/she needs to be sure this change in priorities is genuinely supported at the higher echelons of the Company.)

Who should conduct the Review? I’m a Consultant so of course you know what I’m going to say. But it doesn’t necessarily have to be someone external: provided this person has the necessary skills and experience to conduct such a Study, there can be advantages to using someone inside the Company because you need to foster cooperation, openness and honesty; in short, trust. Most interviewees will find it easier to trust someone they already know, provided they are perceived to be neutral and not attempting to gain a personal advantage by making others look bad. Yes, trust really is the key.

But if you go the internal route, I strongly recommend you do not use anyone currently involved in the ESP operations in question. We are all subject to conscious and unconscious biases, and it’s easier to be neutral when you are not put into a situation of somehow having to “defend” current practice because you are part of it.

Equally important is the avoidance of “Betriebsblindheit“. What this German word describes is how, when we spend long enough in a particular environment, we gradually stop noticing things; we become oblivious to important signs and signals.

That’s why I think nothing beats a “fresh pair of eyes” and an open mind.

The ideal solution, I believe, is a combination of 1-2 Consultants and a Company Representative. The Consultants should be independent in the sense of disinterested, i.e. not employed by an ESP Vendor or other Stakeholder such as a Partner in the Field. He/she should of course have relevant experience – not only technical, but also possess strong interviewing skills. This includes working from a good set of carefully prepared questions designed to maximise the quality of information to be gleaned during interviews, while at the same time being open to follow-up on new and, perhaps unexpected, information. Active listening is a valuable skill. The key here is to be able to listen carefully to responses – as well as body language and what is not being said – so you don’t miss anything valuable because you are too distracted preparing what to ask next.

The Company Representative could be, and in my experience often is, a young engineer not involved in the operations to be reviewed; not an ESP expert who thinks they already know all the answers, but rather someone with an open mind who is motivated, keen to learn and is known within the Company. He/she provides an invaluable role of liaison, for instance logistics (e.g. setting up appointments for interviews – especially with managers of other departments), helping interviewees feel more comfortable about divulging confidential information to an external Consultant. He/she can also contribute to study efficiency by briefing the Consultant on who’s who within the company and how it functions*.

(*Ask yourself this: the last time you moved to a new company, how long did you need to find your feet, to figure out which departments and personnel affect your part of the business, not to mention the ones you don’t normally interact with? Now imagine paying someone who is on a Day Rate – wouldn’t you want them up to speed as soon as possible?)

Summary

The Life Cycle approach to maximising ESP run life has been around a long time. I was first introduced to the concept some two decades ago by a Consultant that I hired to help me address all the challenges revealed by those motor failures mentioned at the start of this blog. (I needed help, and fast!) But I will claim credit for the bicycle chain analogy

I have applied the Life Cycle approach on numerous occasions since becoming a Consultant myself. It has proven to be extremely effective because it is both systematic and holistic. All elements must be reviewed and optimised if the goal is to maximise run-life.

This process is continuous. In general, low-hanging fruit – changes that are easiest and quickest to implement – will be tackled first. More complicated recommendations may take several months to complete. Also note that not every recommendation can necessarily be implemented concurrently. So it’s quite possible that a follow-up Review is desired (or becomes necessary!) before all the recommendations have been fully implemented. (Think: painting the Eiffel Tower.)

Follow-up Reviews can usually be managed in-house, e.g. in the form of a multi-disciplinary ESP Run-Life Improvement Group.

I’ve met Senior Managers who appear to think there’s a kind of magic bullet that will instantly “solve” the issue of poor ESP run-life. They expect that replacing an ESP Vendor or perhaps training a certain individual is all that’s needed. But as I have argued in this article, it’s never that simple.

Working through all the Life Cycle elements can appear tedious but the rewards are there, and they are measurable in the form of improved ESP run-life. Personally, I think the biggest benefit is more intangible than say, “better procedures”, and it’s one of the hardest things to achieve – a change in the corporate mindset. (If you think a 1-year average run-life is acceptable, well… that’s all you’re likely to achieve.)

Changing the company culture starts with people at the top. It requires Management to be seen to take a proactive and positive interest in implementing changes that will help promote ESP run-life: whether it’s aligning goals between departments, encouraging open discussion about areas for improvement without fear of hostility for bringing up uncomfortable truths, more training for staff, or whatever. The end result is a higher level of engagement (buy-in) from those “doing the doing”.

I’ve been an independent Consultant since 2002, but in my previous life as an Operator employee the best Manager I ever worked for summed it up like this. He said,

“Stuart, it’s your job to do the doing, and it’s my job to remove any barriers that prevent you from doing your job. So tell me how I can help, and then get on with it.”

I can’t argue with that.

[1]“Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics”. I used to think this famous quote originated from Benjamin Disraeli, but apparently not: https://www.york.ac.uk/depts/maths/histstat/lies.htm